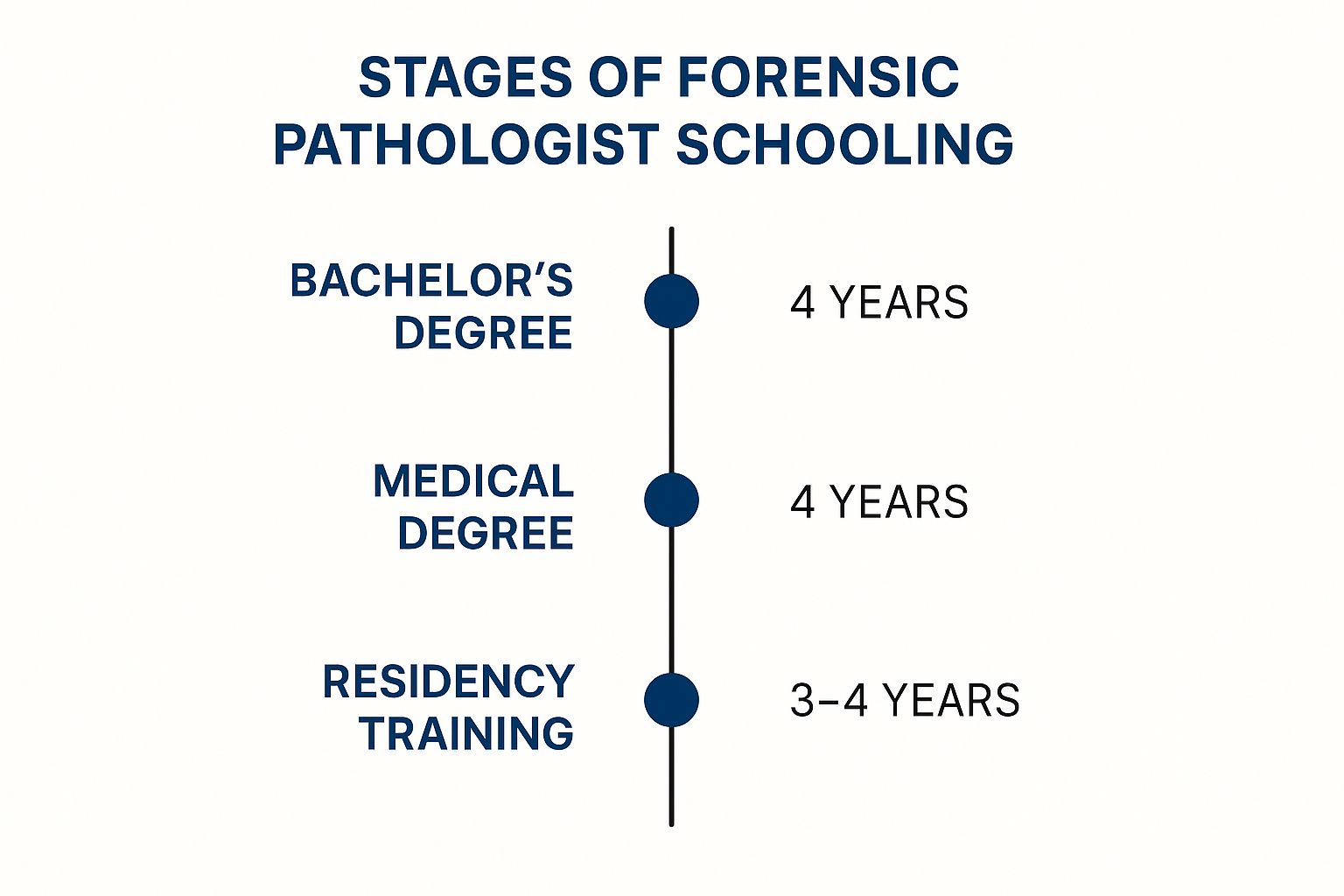

TL;DR: Becoming a forensic pathologist is a marathon, not a sprint. It requires 12 to 14 years of post-high school education and training, including an undergraduate degree, medical school, a pathology residency, and a specialized forensic pathology fellowship, culminating in board certification.

- Total Time Commitment: 12-14 years after high school.

- Key Educational Steps: Bachelor's Degree (4 years) -> Medical School (4 years) -> Pathology Residency (3-4 years) -> Forensic Pathology Fellowship (1 year).

- Essential Degree: Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) or Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (D.O.).

- Critical Skillset: A strong foundation in science, analytical thinking, emotional resilience, and clear communication.

If you are considering a career in forensic pathology, it is essential to first understand the profound commitment involved. This is not a path one chooses lightly; it is a marathon that requires years of intensive education and hands-on training. It is a demanding road, one that necessitates a genuine passion for science, a deep respect for medicine, and an unwavering dedication to seeking truth in the face of loss.

The Educational Roadmap: From College to Certification

The journey is long and structured, with each step building logically on the last. An aspiring forensic pathologist begins with a broad scientific foundation and gradually narrows their focus, acquiring the highly specialized skills needed to perform medicolegal death investigations. This pathway is standardized across the United States, requiring a minimum of 12 years of post-secondary education and training before one can practice independently.

Let’s break down what that timeline looks like.

As this illustrates, becoming a forensic pathologist is a serious, decade-plus investment in one's education. There are no shortcuts.

To provide a clearer picture of the entire journey, this table outlines the major stages you will complete.

Typical Educational Timeline for a Forensic Pathologist

| Educational Stage | Typical Duration | Primary Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Undergraduate Degree | 4 years | Building a strong foundation in sciences like biology, chemistry, and physics. Earning a high GPA is crucial. |

| Medical School | 4 years | Earning an M.D. or D.O. degree. The first two years are classroom-based, followed by two years of clinical rotations. |

| Pathology Residency | 3-4 years | Hands-on training in either anatomic pathology (AP) or combined anatomic and clinical pathology (AP/CP). |

| Forensic Pathology Fellowship | 1 year | Specialized, intensive training in medicolegal death investigation, including performing autopsies and testifying in court. |

| Board Certification | Lifelong | Initial certification after fellowship, followed by ongoing education and recertification to maintain expertise. |

This timeline puts the required dedication into perspective. Each stage is designed to equip a future forensic pathologist with the specific knowledge and practical skills necessary for the immense responsibility of the role.

Clarifying the Role of a Forensic Pathologist

Before proceeding, it is important to clarify a common misconception. A forensic pathologist is a physician—a medical doctor (M.D. or D.O.) who has completed specialized training to determine the cause and manner of death in cases that are sudden, suspicious, or violent.

We are not coroners. A coroner is often an elected official who may or may not possess medical training. We are also not crime scene investigators, who are responsible for collecting evidence at the scene. Our work begins with the decedent, where we apply medical science to find answers.

At its core, our work is to provide objective, science-backed answers. These answers can offer a measure of closure to grieving families and provide crucial evidence for the justice system. It is a profound responsibility that demands more than medical skill; it requires an unwavering ethical compass.

The journey is long and demanding, but the motivation often comes from a deep-seated need to bring clarity to complex situations and provide a voice for the deceased. Understanding the full scope of these educational requirements is the first, most critical part of deciding if this field is right for you.

If you wish to learn more about the day-to-day realities of the profession, you can read more about a career in forensic pathology in another one of our articles.

Laying the Groundwork in College and Medical School

The road to becoming a forensic pathologist is a marathon, and the initial miles are run long before one enters a morgue. Your undergraduate and medical school years are where you forge the foundation—building the scientific knowledge, sharp analytical skills, and personal resilience this career demands.

Think of this period less as a checklist and more as an opportunity to deliberately shape yourself into both a physician and an investigator.

Choosing Your Undergraduate Path

There is no "forensic pathologist" major. What is absolutely necessary is a rock-solid science background. Most successful medical school applicants major in a discipline that provides rigorous scientific training. The first step on this journey involves several years of undergraduate study, where a strong science curriculum is key for understanding the role of colleges and universities in preparing for medical school.

What should you major in? The most common and effective majors include:

- Biology: This provides a deep understanding of human anatomy, physiology, and cellular processes.

- Chemistry: This is crucial for understanding toxicology and the biochemical changes that occur after death.

- Forensic Science: This can offer a valuable introduction to the principles of evidence, but you must ensure you are also completing all pre-medical requirements.

However, a well-rounded education will make you a far better forensic pathologist. I strongly recommend supplementing your science coursework with the following:

- Public Speaking: This is invaluable. You will be required to stand in court and deliver clear, objective testimony.

- Criminal Justice: This provides a crucial framework for the legal system in which you will operate.

- Psychology or Sociology: These courses offer powerful insights into human behavior and the complex social situations that often surround a person's death.

The ability to explain complex medical findings to a jury of laypeople is just as critical as the ability to perform a complex dissection. Your undergraduate years are the perfect time to build that communication skill set.

Excelling in Medical School

Admission to medical school is highly competitive. Admissions committees look for the complete package: excellent academics, relevant experience, and strong character. A high GPA (especially in science courses) and a strong MCAT score are the initial benchmarks.

Your personal statement and experiences are what differentiate your application. Shadowing a pathologist, volunteering in a hospital, or working in a research lab demonstrates a genuine interest and a realistic understanding of the profession, including its emotional demands.

A common question is whether to pursue a Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) or a Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (D.O.). Both are rigorous, fully-licensed medical degrees that provide a path to this career.

| Degree Path | Focus | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| M.D. (Doctor of Medicine) | Follows a traditional allopathic approach, focused on diagnosing and treating disease. | Qualifies for all U.S. medical residencies, including pathology. |

| D.O. (Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine) | Includes allopathic training plus a holistic approach emphasizing the musculoskeletal system. | Qualifies for all U.S. medical residencies, including pathology. |

Both M.D. and D.O. graduates are equally eligible to become board-certified forensic pathologists. The choice is a matter of personal preference regarding educational philosophy.

The first two years of medical school are primarily classroom-based, building an advanced understanding of anatomy, physiology, and pathology. The final two years are dedicated to clinical rotations. This is your opportunity to seek an elective rotation in a medical examiner’s office or with a hospital’s autopsy service. This experience is critical for confirming if this is the right field for you. It provides a glimpse into the daily work and profound responsibility of the profession, preparing you for the next, even more intense, stage: residency.

Mastering the Science During Pathology Residency

After medical school, the practical training begins. A pathology residency is where the textbook knowledge acquired over years is tested in the real world. This is an intense, multi-year apprenticeship where you transition from theory to daily, hands-on practice, building the foundational skills that will define your career.

This training period typically lasts three to four years and is characterized by supervised, practical work in a hospital or medical center. It is a demanding but absolutely crucial phase on the path to becoming a forensic pathologist.

Anatomic vs. Clinical Pathology: A Critical Distinction

Pathology residencies are structured around two core disciplines: Anatomic Pathology (AP) and Clinical Pathology (CP). While many residents pursue a combined AP/CP track, anyone planning a career in forensics must focus on mastering anatomic pathology.

- Anatomic Pathology (AP): This is the core of forensic work. It involves the examination of tissues and organs, both with the naked eye (gross examination) and under a microscope. This includes biopsies, surgical specimens, and, most importantly, hospital autopsies.

- Clinical Pathology (CP): This is the domain of the clinical laboratory. It deals with the analysis of bodily fluids like blood and urine, covering areas such as chemistry, microbiology, and blood banking. While vital for patient care, it is not the primary skillset for death investigation.

For an aspiring forensic pathologist, mastery of anatomic pathology is non-negotiable. The skills honed here—examining organs, identifying disease, and understanding how injury manifests in human tissue—are precisely what you will use every day in a medical examiner’s office.

A Glimpse Into the Daily Life of a Resident

A resident’s schedule consists of a series of rotations, each designed to provide exposure to a different aspect of pathology. One week, you might be in surgical pathology, diagnosing cancer from tissue removed in surgery. The next, you could be in cytopathology, examining individual cells for malignancies.

For a future forensic pathologist, the most important rotation is the autopsy service. Here, you will perform hospital autopsies under the supervision of an attending pathologist. These cases are typically natural deaths, but they provide invaluable experience in dissection, documenting findings, and correlating a person's clinical history with postmortem findings. Our guide on the job description of a pathologist dives deeper into what this work entails.

The skills you develop during residency extend far beyond the scalpel and microscope. You learn to write clear, concise, and defensible reports—a skill that is absolutely critical when your findings become evidence in a court of law.

Maximizing Your Residency for a Forensic Career

To build a strong resume for a forensic fellowship, you must be proactive and strategic during your residency. This is your chance to actively shape your future.

Here’s how to make the most of this time:

- Seek Out Medicolegal Cases: Volunteer for any hospital autopsy that has potential legal implications, such as an unexpected death following a routine procedure or an in-hospital accident.

- Network with Experts: If any attending pathologists at your institution are board-certified in forensics, seek their mentorship. If not, request an "away rotation" at a local medical examiner’s office for direct exposure.

- Become Meticulous with Documentation: Treat every report you write as if it could be presented in court. Learn to take high-quality photographs of your findings and use objective, unambiguous language to describe them.

- Present Your Work: Find an interesting case and submit an abstract to a pathology conference. This forces you to organize complex medical information and present it clearly to an audience—excellent practice for explaining findings to a jury.

Residency is far more than a training program; it is your apprenticeship in the science of death investigation. The habits, skills, and professional connections you forge during these years will directly prepare you for the final step in your journey: the forensic pathology fellowship.

The Forensic Pathology Fellowship: A Year of Specialization

After years of foundational science, medical school, and a broad pathology residency, the fellowship is where all your training converges. This is the year you truly learn to think and act like a forensic pathologist. This intensive, one-year program is the final, most critical piece of your formal training—an immersive experience that transforms you from a pathologist who understands disease into a medicolegal expert who investigates death.

This specialized training almost always takes place on the front lines, in a medical examiner's or coroner's office. It is a world away from the hospital setting. In residency, your autopsies often confirm what clinicians already suspected. In fellowship, every case has legal implications.

From Resident to Investigator: The Core Transition

The shift in responsibility during fellowship is significant. You are no longer just a trainee observing from the sidelines; you are an active investigator with real autonomy, albeit under the supervision of board-certified forensic pathologists. Your caseload will be diverse and demanding, reflecting the full spectrum of circumstances that fall under a medical examiner's jurisdiction.

The entire journey to this point is a marathon, spanning at least 12 to 13 years after high school. This one-year fellowship is the capstone, offering essential hands-on experience in morgues and at death scenes, training you to conduct meticulous autopsies and collect evidence. For a deeper look into the comprehensive training, see this overview of the full journey to become a forensic pathologist.

Your day-to-day work is a mix of science, investigation, and communication:

- Conducting Medicolegal Autopsies: You will perform hundreds of autopsies on individuals who died suddenly, violently, or under suspicious circumstances.

- Scene Investigation: You will accompany investigators to death scenes. Witnessing the context firsthand is invaluable and changes how you interpret your findings back at the office.

- Evidence Interpretation: Your role is to connect the dots. You will integrate toxicology reports, police records, medical histories, and your autopsy findings into a cohesive, evidence-based conclusion.

- Courtroom Testimony: A unique skill in itself, you will begin learning how to present your findings in a clear, objective, and defensible manner before a judge and jury.

This year is less about mastering new dissection techniques and more about developing rock-solid judgment. You learn to spot subtle patterns, ask the right questions, and build a logical, evidence-based narrative explaining not just how someone died, but in what manner.

The Gravity of the Work: A Look at Real-World Scenarios

The cases you handle will be real-life tragedies and complex legal puzzles, each demanding a meticulous and unbiased approach.

One day, you might examine an elderly person found deceased at home. The initial assumption may be "natural causes," but your examination might uncover subtle signs of neglect, transforming the case into a criminal investigation. The next day, you could work on a motor vehicle collision fatality, tasked with determining if the crash caused the death or if a sudden medical event, like a heart attack, caused the crash.

A fellow routinely encounters cases such as:

- Suspected Homicide: A young adult is found with a gunshot wound. Your job is to trace the wound path, recover the projectile for ballistics analysis, and document every other injury.

- Workplace Accident: A construction worker falls from scaffolding. Was it an accident, a medical event, or equipment failure? Your findings will provide the answer.

- Infant Death: The sudden, unexplained death of an infant is one of the most challenging cases. It requires an incredibly careful and compassionate examination to distinguish between natural causes, accidental circumstances, and, tragically, non-accidental injury.

- Overdose Investigation: You will correlate toxicology results with autopsy findings to confirm the cause of death. Identifying the specific substances involved is also critical for public health surveillance.

Every case requires scientific rigor and also takes an emotional toll. The fellowship year is designed to build your resilience alongside your skills, preparing you to handle the immense weight of this responsibility with professionalism and empathy. This final training is the bridge that takes you from being a doctor to becoming a trusted voice for the deceased within our justice system.

Earning Your Board Certification and Committing to Lifelong Learning

Completing a forensic pathology fellowship is a significant accomplishment, but the journey is not yet over. The capstone of your entire training is earning board certification. This is the official credential that validates your expertise, marking your transition from a trainee to a fully qualified specialist. In this field, it is the gold standard.

This final phase is overseen by the American Board of Pathology (ABP) in the United States. Achieving their certification after your residency and fellowship is a critical milestone. It is a formal assurance to the public, law enforcement, and the courts that you have met a national standard of professional competence. You can get a sense of the benchmarks by reviewing the typical requirements for a forensic pathologist.

Navigating the Board Certification Exams

The path to becoming a board-certified forensic pathologist is a two-step process. First, you must become certified in anatomic pathology. This involves a challenging examination covering everything learned in residency—disease processes, surgical pathology, and complex autopsy procedures.

Only after passing that exam can you sit for the forensic pathology subspecialty board examination. This is a highly focused, one-day test designed to evaluate your specific expertise in medicolegal death investigation. It is not about general pathology; it is about the unique questions forensic pathologists must answer.

Key areas covered on the forensic pathology board exam include:

- Wound Interpretation: Distinguishing between a gunshot wound, a stab wound, and blunt force trauma is just the beginning. You must interpret injury patterns to reconstruct events.

- Toxicology: This involves more than reading a lab report. It requires understanding how drugs and poisons affect the body and contextualizing those findings with the autopsy.

- Forensic Science Principles: You need a solid working knowledge of adjacent fields like DNA analysis, ballistics, and trace evidence to connect your medical findings to the larger investigation.

- Medicolegal Procedures: This tests your grasp of the legal and ethical framework governing the work of medical examiners and forensic pathologists.

Passing both exams requires months of intense study, but becoming "double-boarded" is an essential requirement for practice in this field.

Board certification is much more than a certificate for your wall. It is a public promise of your commitment to excellence, objectivity, and the ethical practice of forensic medicine. It signals that your skills and knowledge have met a rigorous national standard, giving your findings and testimony the credibility they require.

A Career Defined by Lifelong Learning

Medicine and forensic science are constantly evolving. New technologies emerge, our understanding of disease deepens, and novel drugs of abuse appear. Consequently, a forensic pathologist’s education never truly ends. This commitment to continuous learning is formalized through a process called Maintenance of Certification (MOC).

MOC is the system that ensures board-certified pathologists remain current with the latest developments. It is an ethical obligation to the communities we serve.

Activities involved in Maintenance of Certification often include:

- Continuing Medical Education (CME): Regularly attending conferences, participating in workshops, and reading scientific journals to stay informed.

- Periodic Examinations: Some boards require recertification exams every several years to ensure continued competency.

- Practice Improvement Projects: Activities that encourage assessment and improvement of one's own work, such as participating in peer reviews of challenging cases.

This ongoing educational demand ensures that our work for the justice system is always grounded in the most current and reliable science. It is how we maintain our promise to the families we serve that our expertise will remain trustworthy throughout our careers.

Answering Your Questions About a Career in Forensic Pathology

The road to becoming a forensic pathologist is a marathon, and it is natural to have questions before taking the first step. This section addresses some of the most common inquiries.

How Long Does It Realistically Take to Become a Forensic Pathologist?

There are no shortcuts; this is a long-term commitment. From your first day of college to becoming a board-certified forensic pathologist, you should expect to spend 12 to 14 years in education and training.

Here is the typical timeline:

- Undergraduate Degree: 4 years, with a strong emphasis on science.

- Medical School: 4 years to earn your M.D. or D.O.

- Pathology Residency: 3 to 4 years learning the foundations of anatomic pathology.

- Forensic Pathology Fellowship: 1 year of specialized, focused training in medicolegal death investigation.

Each stage builds directly on the previous one.

Is a Forensic Pathologist Just Another Name for a Coroner?

This is one of the most common misconceptions, and the difference is significant. A forensic pathologist is a physician. We are medical doctors who have completed the extensive training detailed above to become experts in determining the cause and manner of death. Our conclusions are based on medical science.

A coroner, in contrast, is often an elected official. In many jurisdictions, a coroner is not required to have any medical training. While they hold the legal authority to sign a death certificate, they rely on a forensic pathologist to perform the autopsy and provide the medical evidence. We perform the scientific investigation; they often handle the associated legal administration.

Can I Pursue This Career with a D.O. Degree?

Yes, absolutely. A Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (D.O.) degree is an equally valid pathway into this field as a Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) degree. Both degrees qualify you as a physician, and graduates from both programs are eligible for the same pathology residencies, forensic fellowships, and board certification examinations from the American Board of Pathology.

Once you enter residency, the distinction between M.D. and D.O. becomes irrelevant. Your skill, work ethic, and dedication are what matter.

The legal system—and the families we serve—rely on objective, scientifically sound investigations. That standard is independent of whether a physician is an M.D. or a D.O. It is about the quality and integrity of the work.

What Skills Are Most Important Beyond Academics?

Excelling in this profession requires a specific set of skills that are not always taught in a textbook.

Key traits include:

- Meticulous Attention to Detail: You must be the type of person who notices the smallest inconsistencies, as a tiny fiber or a subtle bruise can change the entire interpretation of a case.

- Strong Analytical and Problem-Solving Skills: The work is akin to solving a complex puzzle. You must constantly synthesize information from the autopsy, toxicology reports, and scene investigation into a coherent narrative.

- Emotional Resilience: You will encounter tragic and difficult situations daily. The ability to compartmentalize and maintain professional objectivity while treating every decedent with dignity is essential.

- Effective Communication: One day you may be writing a highly technical report, and the next you may be on a witness stand explaining complex medical findings to a jury with no medical background. Clear, confident communication is vital.

Ultimately, unwavering integrity is the most important attribute. As a forensic pathologist, you speak for the deceased, a responsibility that demands nothing less than complete honesty and objectivity.

At Texas Autopsy Services, we understand that navigating a loss is incredibly difficult, and finding answers is a critical part of the process. If you have questions about private autopsy services, our team of compassionate experts is here to provide clarity.

Please feel free to contact our team to discuss your needs.